It’s hard to avoid the chatter around the concept of ad blocking if you work in the digital marketing industry these days. Since Apple released iOS 9 last fall and started approving ad blocking apps, the news has been full of the impending crisis that ad blocking will cause. While ad blocking is a serious issue that can’t (and shouldn’t) be ignored by those of us in the ad industry, the result of it won’t be the death of online advertising. Quite the opposite will ultimately happen, in fact. Ad blocking will make online advertising (and with it the whole of the Internet) better for everyone.

First, let’s remember that ad blocking is not new. Ad blocking software has been available and in relatively wide use in desktop browsers for years. In fact, you could argue that popup blockers were the first ad blocking technology deployed way back in the early online days. Those annoying early Internet popup ads are actually a very instructive parallel for what we’re experiencing today and how we can overcome it. Ad blocking is today, just as it was then, an allergic reaction to bad online advertising. The motivation to go out of your way to install something that shields you from marketing messages requires a pretty strong stimulus, and so much of the stuff that’s out there in this industry right now, sadly, fits the bill.

So what does bad advertising look like? I think we all have a pretty good idea of that, as we’ve all no doubt been exposed to it. Bad advertising is intrusive. It’s deceptive. It’s overly interruptive to our online activities. The quintessential example of this is the click-bait site, and the Internet today is overrun with them. While there are a lot of factors that have contributed to the rise of properties like this, I have to look first at the marketing community. Programmatic display advertising technology has intoxicated us with targeting possibilities and blinded us with the promise of cheap impressions. The intention here has been mostly good. Agencies want to deliver value to their clients by reducing cost and eliminating waste. Client-side marketers want to merchandise value and demonstrate wins and efficiencies. What we’ve all lost sight of is that the experience of how that advertising is delivered is really, really important, and we are feeling the effects of that as our audiences flock to these technologies to block us. And make no mistake about it; they are blocking us. That should sting, and our posture as an industry right now should be that of someone who has just been publicly chastised. We have to take responsibility for this and do better. Let’s take a look at how we can do that.

First of all, as marketers, we have to demand more of our networks. The race to the bottom in terms of impressions and clicks in online display has degraded the quality of those commodities tremendously. As usual, when something seems too good to be true, it probably is. Just look at some of the reports of how these programmatic campaigns are performing by traditional branding measures. As the people planning and executing these media buys, we have to understand and act on the fact that all impressions are not equal. I am consistently seeing ads for big brands on these low-quality click-bait sites (never mind why I’m on click-bait sites; it’s not important). Those impressions get stacked into false page views in intentionally clunky slideshows designed to get you to inadvertently click on that retargeting ad you just saw for the 12th time this session. This is bad advertising. It deserves an ad blocker, and we can do better. Be legalistic about things like frequency capping. Weed out bad sites through exclusion. Report them to the networks, and starve them of impressions. They will either go away or improve their practices. Not only is this the right thing to do for the users, it is clearly the right thing to do for brands. Appearing in this fashion is waste. It’s ineffective. It does not matter how low you can get your CPM when what you’re buying is absolute garbage. If we strive to make advertising targeted, relevant and meaningful, those efforts will have the dual benefit of improving client results and the user experience.

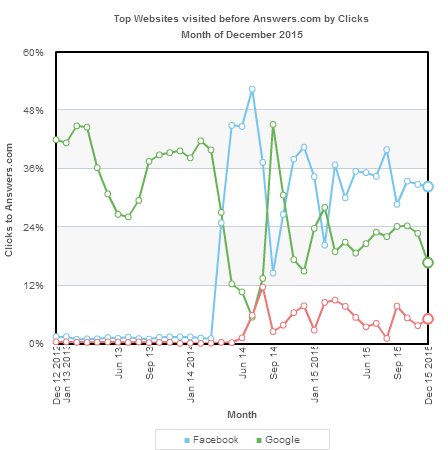

I put what marketers need to do first for a reason. It’s the most important piece of the puzzle here, but it’s not the only one. Publishers and ad networks have a big role in this as well. Accepting ad dollars from sites that exist only to monetise display impressions is, to put it mildly, problematic. Propping up those business models by continually allowing non-paid traffic from major web properties is also contributing to the environment that has users blocking ads. Google has been a leader in this area. First of all, they have very strict quality guidelines for advertisers. The prohibited practice policy section for AdWords clearly states that “ads promoting sites or apps that offer little unique value to users and are focused primarily on traffic generation” are not welcome. If all networks and publishers would simply enact and adhere to that policy, the need for ad blockers would materially diminish. Beyond that, Google has put a monumental amount of effort behind weeding out this kind of junk in their organic search results. The series of Panda updates over the past five years have been targeted at sites with thin content that exists largely to aggregate and monetise traffic. I don’t mean to pick on a single site, but let’s take Answers.com as an example. Just take a look at this traffic graph from Hitwise:

Answers.com started as an organic search play to satisfy informational queries (“why are french fries called french fries?” and the like). As you can see from the above chart, this site at one time got nearly half of its traffic from Google. Almost all of this was organic. However, they took a huge hit right when a major iteration Google’s Panda came out in the spring of 2014. This is because Google views their content as being low quality and existing primarily to aggregate and monetize traffic rather than provide value to users. The data shows that Answers.com, after some ups and downs, now gets less than one-quarter of its traffic from Google. However, you can also see from the graph that they found another outlet for their business model in Facebook when they saw Google fall of the map. At this point, they also pivoted (despite their name) from a question and answer-based site to one focused on celebrities and listicles – content that plays quite well with the social media crowds. The question for Facebook then is, why are they propping up this model when Google has made a conscious decision not to?

Further to that point, Google is wearing its ad quality decisions as a badge of honour. They just released their 2015 “Better Ads” report where they tout the fact that they’ve blocked 780 million ads from their networks for policy violations, using more than four billion pieces of user feedback. While other publishers and networks may have similar efforts in the same direction, Google is making the user experience a centrepiece of their advertising practices, and everyone else will no doubt continue to follow. Couple that with their commitment to ad viewability, and you can see that Google has really doubled down on its quality promises to both advertisers and users.

That brings me to the last, but certainly not least, an important component in this equation: the user. Ad blocking is the collective user base throwing its hands in the air and saying enough is enough. Things have gotten so out of hand, especially when you’re dealing with the limited real estate on the now preeminent mobile screen, that a significant chunk of users are going out of their way to opt out of marketing messages altogether. I don’t blame them, but I do believe that the majority of these users are reasonable and recognise that there is an understood exchange of value going on in the modern Internet experience. The really valuable content online is almost exclusively funded by marketing. With a few notable exceptions, users have proven unwilling to pay for web content. Ultimately, accepting the advertising that goes along with the content you want to access is part of the deal. While ad blocking is a natural reaction to the abuse of that understanding by all too many players in the space, as marketers, publishers and networks endeavour to do better (as I believe they will), users will come back into the fold (or at least stop exiting the fold). The exchange of valuable online content for access to eyeballs and user data will continue, and it will, over time, be course-corrected by the scare that ad blocking has created.

Ad blocking is more or less a form of virtual protest on the part of beleaguered users. They are demanding more from those who make a living shaping the online experience today, and they are right to do so. The response from the industry that many of us depend on and hold dear should not be focused on how to get around ad blockers, but rather how to eliminate the need for them. Working together, marketers, publishers, ad networks and ad tech companies can consistently deliver marketing messages in a way that respects the user experience and preserves the commerce environment that will make a better Internet possible.

For more information, contact DAC!